Once upon a time, I felt it necessary to be “correct” all the time. Necessary – and vitally important. To know how to smoothly maneuver any situation, to say some polysyllabic constellation of words to dazzle and open doors. It was my own small way of manipulating the world, a strange skill I learned to rely on early.

I have never considered myself charming, to be clear, but I felt that, through my hyperarticulateness and apologetic tone, I could deal with whatever I had to. I would show people how good I was, and through impressing them or saying the right thing, they would help me solve my problems.

It’s a difficult thing to keep up. Even if you are naturally polysyllabic and hyperarticulate, it takes a lot of energy. It’s not a sustainable tactic.

I began to walk away from being this way a couple years ago. It changed everything – it lightened my heavy introversion, because being around other people wasn’t such an energy suck. It paved the way to easier and more genuine interactions with everyone from my nearest and dearest to the cashier at QFC. I embraced it, and I opened myself to being awkward (once a life-bending fear) and incomplete. I opened myself to actually being real with people. I congratulated myself on being past this old hindrance. Haven’t I done so well.

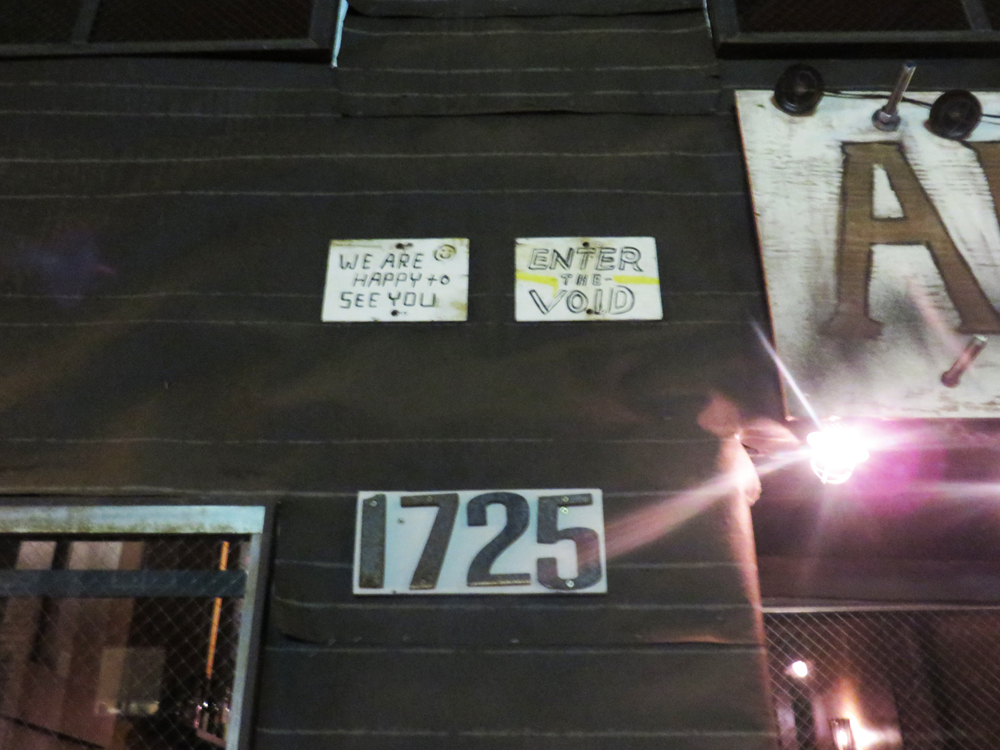

In Paris last year, I realized how far that was from the truth. I may not try to dazzle people with my glittering utterances anymore (or not all the time, anyway), but I am made of words, and to have to get by without them left me unprepared for anything – and panicked at times. My first two or three days were spent with at least a mildly elevated heartbeat. What if something happened? What if someone misunderstood me?

Beginner’s mind: it does not come easily to me.

It was easier this year. Because we went to a trilingual country where it’s in everyone’s financial interest to speak at least business English. Because my French is somewhat better than nonexistent now. But mostly, really, because I calmed down. Once upon a time, that the housekeeper who checked us into our Brussels studio didn’t know English would have left me stricken. What if we missed some vital detail? What if we have a question or an emergency later?

What if she doesn’t know how smart I am?

Oh.

Instead, I was able to admire how she was able to pantomime everything from how to work the complicated locks to where the coffee is (and how good it is) to how to work the TV. Her job is to deal with Frenchless foreigners; she performs it beautifully and with good humor. And instead of feeling mortified at being inadequate, I was able to enjoy the particular skill she’s had to cultivate and to marvel at how much I was able to learn without words – and how happy I was to pick out the French I understood.

It was a great welcome to Brussels.

I think what makes a person able to travel and really enjoy it is the skill to laugh at these shortfalls. To enjoy the gaps that exist between people and cultures, but also to celebrate when they’re bridged (perhaps using a mix of French, English, and Spanish, which happened to us at the kaiten-style Spanish tapas restaurant in central Brussels – a good meal, enjoyably delivered by lovely people).

At the end of a trip, yes, I confess I’m glad to return to where I know when the bars close and what’s sold at a pharmacy vs. the grocery store and how to pay the check in a restaurant. But it’s a flush of gratitude, a fluency returned, and there’s pleasure in that too. I know this. I can do this right.

I hope that, one day, beginner’s mind comes naturally to me. I admire it so in other people.

In the meantime, if I can look past my panic in a moment, I can see a crossroads. And I choose, over and over, the path of laughing and laughing, and trusting that most of us just want everything to turn out ok.